The Banal Evil of Atrocity Photography

In the dark genre of self-reported atrocity photography, governments take pictures of their crimes and file them away in an act of simultaneous remembering and forgetting. I wrote this essay for the art magazine Hyperallergic.

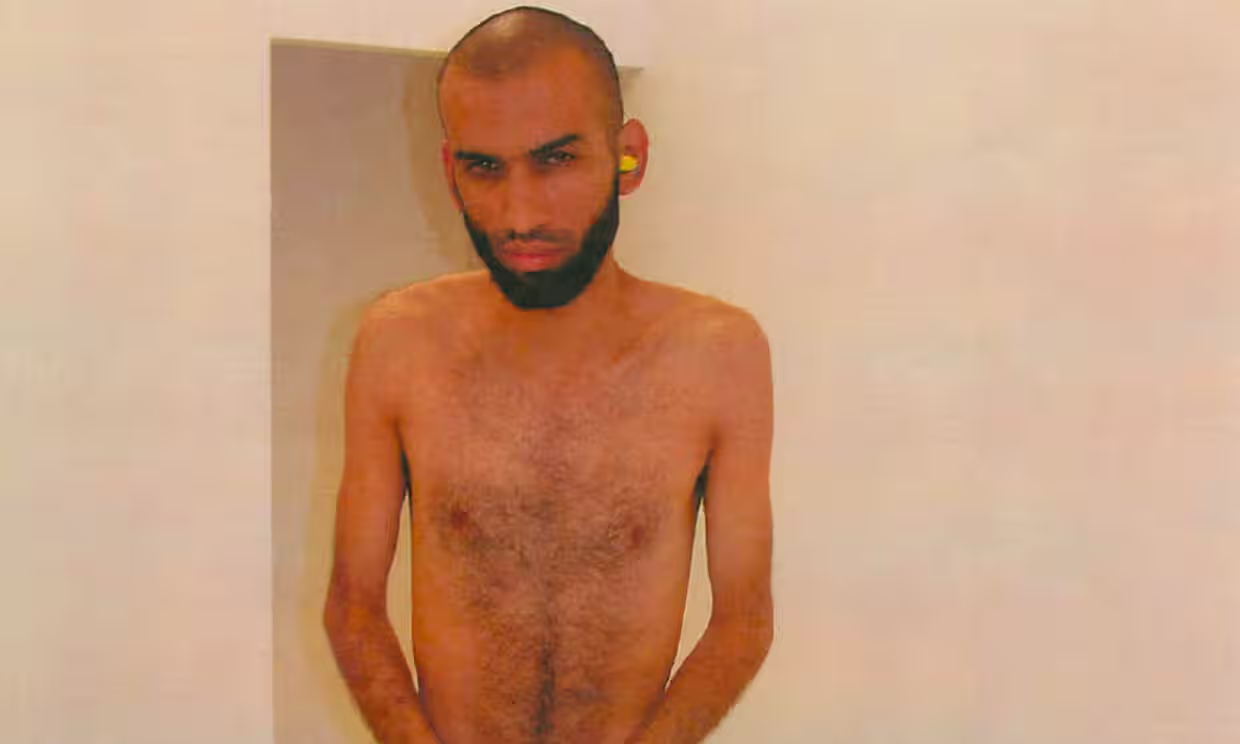

An emaciated man stands alone. He’s naked and in an all-too-white room. The hair on his head has recently been shaved, though his beard is full. The handcuffs shackling his wrists appear oversized for his small frame. A yellow earplug is jammed in only one ear.

This photograph is the public’s first, and so far only, look at a War on Terror detainee in a Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) black site: a secret detention center set up to hold and interrogate prisoners who have not been charged with a crime. It’s a surprising image, stark and overexposed, both in terms of how bright the photograph is and how naked the man is. Someone employed by the CIA took this photograph, though we don’t know who. But we do know why it was taken, and who it is in the frame.

His name is Ammar al-Baluchi, a detainee at Guantánamo Bay currently facing capital charges for the 9/11 attacks. This photograph, likely from 2004, is from the period before he was transported to the United States’s offshore penal colony in 2006. Baluchi was one of at least 119 Muslim men held incommunicado by the CIA for years in its global network of clandestine black sites, where he and at least 38 others were repeatedly subject to “enhanced interrogation techniques,” a US-government euphemism for torture.

From May 2003 to September 2006, Baluchi was secretly shuffled between five black sites, including one in Romania, where this photo is believed to have been taken. (The photo, recently declassified, was provided to me by Baluchi’s lawyers, who added the black band across his midsection to preserve his dignity. I broke the story surrounding the photograph and Baluchi for the Guardian earlier this year.) Whenever any of these Muslim men were moved, CIA protocol dictated that field officers photograph each one, both naked and clothed, “to document his physical condition at the time of transfer.”

The image before us isn’t just any photograph. It’s visual evidence of crimes authorized and committed by the United States government, an entry in the annals of self-reported atrocity photography. In all, the CIA took some 14,000 photographs of the agency’s black sites around the world, but we, the public, have never been able to see any of them until now.

There are plenty of examples of this macabre genre. Israel produces it. So does Syria’s Bashar al-Assad. As did the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. The Nazis. The Soviets. The French. Governments of different political leanings have contributed to this dark archive, uniting the magical technology of the camera with the awesome power of detention and even death. They take pictures of their own crimes and immediately file them away, in an acrobatic technocratic act of simultaneous remembering and forgetting.

The question is why. A photograph, presumably, is meant to be seen. These images, on the other hand, were intended to record but almost never to be viewed. They were certainly never meant to be seen by the public.

Of course, anyone who has used their phone camera to take a picture of a receipt knows that a photograph doesn’t have only a public function. It can also operate as a trace of memory and documentation of a transaction. Self-reported atrocity photographs, indeed, fulfill the record-keeping needs of a government bureaucracy. The fact that the CIA was using black sites was revealed to the public in 2005, but it was not until 2015 that the photo archive documenting them was exposed. In response to that revelation, a US government official described the photographs as having been “taken for budgetary reasons to document how money was being spent.” Behold the banality of bureaucratic evil…

Click here to read the entire essay.